Now What? The Five Crises Confronting a Post-Strike Hollywood

Hollywood’s "summer of strikes" may be about to wrap, but don’t pop the champagne just yet. Existential issues still loom large.

As brutal as 2023 has been for the entertainment industry, it’s possible the town will someday look back on this moment wistfully. And not just because of the picket line solidarity or cozy mogul hangs in the bargaining room.

The strikes helped earn gains for Hollywood workers in such areas as streaming residuals and AI, just as they cost the national economy more than $5 billion. But the walkouts also marked the decisive end to a bullish and ultimately unsustainable chapter in Hollywood, an era that was already on its way out when writers put their pens down May 2. This was an age when money flowed freely and companies vying to build their nascent streaming platforms competed for talent with generous and plentiful overall deals. An era when 599 scripted shows a year kept 599 different casts and crews employed. One when actual human beings — not AI — did the creative work of making films and television shows.

But that heyday has officially ended, thanks to unsexy factors like high interest rates and industry consolidation, and the strikes gave studios cover to drop their unwanted deals and trim their budgets. The new, post-strike Hollywood is going to be a much leaner one. “This business has now gone through a pandemic, a dual strike and an economic downturn, and the companies have sobered up,” says one agency executive. “The business is getting tougher. For the working-class writer, director, producer, you’re going to see a contraction.”

Post-strike Hollywood also is likely to transition from what has been a strange era in the entertainment business, one when success was often divorced from compensation, thanks to the streaming formula of big up-front paydays without the prospect of performance-based rewards — or even information about how a show or film did on a platform. It’s a system, many industry sources say, that led to a lot of crap. “Where was the incentive to stay on budget or make something great?” asks an agency source.

“There needs to be more of a focus on quality,” says Avatar producer Jon Landau. “That doesn’t necessarily mean tentpole. Whether it’s a big movie or TV show or a small one, we have to make it good.”

Post-strike, expect companies to be pickier about what they make and talent and financiers to be more closely aligned on fiscal responsibility and quality. For some creators, more guardrails and feedback will be welcome. “People are hungrier now,” says producer Todd Black. “Writers are, producers are, and studio executives are. I think we’re going to see over the next couple of years, hopefully, more productivity and more selectivity, and in some ways, I think it’s a good thing.”

In the meantime, however, the industry must still grapple with five crises the strikes might have overshadowed but certainly did not solve. — Rebecca Keegan and Chris Gardner

-

Streaming Is a Lousy Business

Image Credit: Peter Kramer/Peacock/NBCU Photo Bank via Getty Images Streaming is awesome. Consumers can watch what they want whenever they want. The fierce competition between services means more choices than ever. And the drive for scale means that streamers have been available at a bargain price, with the ability to cancel or resubscribe at will.

There’s just one problem: The streaming battles took very lucrative entertainment giants and made their rich profits vanish faster than CNN+.

The so-called “streaming wars” really trace their origin to a few fateful months in 2017 and 2018. Yes, Netflix had been serving original content for a decade before that, but in 2017 its streaming business kicked into high gear, with annual net income jumping from $186 million to $559 million (it would double again to $1.2 billion in 2018). Its stock price, which opened 2017 at about $130 per share, would soar to more than $360 in 2018 as Wall Street began valuing the company as a tech platform, giving it a multiple rivaling the likes of Google and Facebook.

Netflix’s success panicked Disney into announcing in 2017 that it would pull all its content from Netflix and launch what would become Disney+. In the aftermath of that debut in 2019, the floodgates opened, with NBCUniversal introducing Peacock and the arrival of Paramount+ and HBO Max (now Max).

The result has been tens of billions of dollars flowing into streaming content and away from linear TV … and massive losses for the legacy media companies that entered the space. Comcast, Disney, Warner Bros. Discovery and Paramount lost a combined $10 billion on their streaming services in 2022, according to a review of their annual reports. Only Netflix reported a profit: $6.5 billion. And some, like Paramount+ and Peacock, have yet to see their losses peak.

It’s a dire situation, particularly with Wall Street no longer valuing streaming companies as tech giants. And it’s a situation made worse by the WGA and SAG-AFTRA strikes, which closed the pipeline for TV shows and films.

It also raises an interesting question: Can streaming even work as a business model?

Speaking to investors and analysts Sept. 19 at Walt Disney World, Walt Disney CEO Bob Iger argued that indeed it could. When Iger laid out four key priorities for his company, making its streaming business profitable was at the top of the list.

“The company plans to make less content and spend less on what it does make, though getting key franchises like Star Wars back in theaters is a priority,” wrote JPMorgan analyst Phil Cusick in a Sept. 20 note, adding that he expects Disney+ to turn a profit by the end of fiscal 2024.

A top streaming executive tells THR that they believe profitability will come, led by advertising, and from getting “the value proposition right.” Many services launched at low prices to lure as many subscribers as possible as quickly as possible. That’s changing, and not only are the prices rising, but they are increasing in a way designed to drive subscribers to ad tiers, where these companies can further monetize users.

There’s a reason that Netflix and Disney+ adjusted their prices to make it more expensive to avoid ads, and there’s a reason Amazon is adding advertisements to Prime Video. They want consumers on those ad tiers (or to pay dearly for the privilege of opting out). Turns out, streaming is hard, but advertising remains a good business to be in.

There are a few encouraging signs that streaming can be profitable, if not quite as lucrative as the cable TV business model it replaces.

Netflix’s profits continue to grow, and for the first time a mainstream service from a legacy media company should turn a profit. Max, the service from WBD, was just about to break even in Q2, and it’s on track to turn a profit this year, CEO David Zaslav told investors during the company’s most recent earnings call.

WBD, of course, was particularly aggressive about slashing costs last year, including removing TV shows and films from the service to avoid paying for shows with little traction.

If the other legacy media companies are a year or so behind WBD, that tracks. Peacock and Paramount+ are aiming for breakeven by the end of next year, as is Disney+, though the impact of the strikes — as a help or a hindrance to this goal — remains to be seen.

And then there’s the Charter Spectrum wild card: If the cable giant is successful in bundling together all the entertainment streaming services, as it’s doing with Disney+, the legacy companies might just be able to find their way to profitability the old-fashioned way: by letting a cable company sell it all together.

Some of the most popular shows on streaming are from the late 1990s and early 2000s anyway (Friends, Grey’s Anatomy, The Office). Why not bring back the business model, too? — Alex Weprin

-

Peak TV Is Over. So Is Peak Pay

Image Credit: Lara Solanki/Netflix For nearly a decade, John Landgraf had been standing on stages telling anyone who would listen that there was too much TV being made.

The FX chairman coined the term “Peak TV” in 2015, a year that saw 420 scripted series hit our television screens. He miscalculated, of course. Aside from pandemic-affected 2020, the total has risen every year since, with 2022 bringing 599 scripted series to viewers. Then came the Wall Street wake-up and the collective realization that making money matters and, finally, the strikes, and the industry is now firmly on the other side. Nobody knows whether the business will ultimately contract by 10 percent or 50 — what everybody can agree on is that less will be made everywhere.

Already, the once-frothy overall deal market had been cooling, though studios used the strike to shave several months off certain pacts and quietly let others expire. Going forward, studio sources suggest they won’t be as quick to jump into overalls, certainly not for the mid-level co-executive producers and EP types. “Deals are going to be connected way more to ‘Wow, your pilot’s fucking great,’ or ‘The show premiered and it’s fucking great, let’s lock this person up,’ ” says one seller, who echoes a chorus of sources in saying that big deals will likely have more bonuses tied to productivity and success baked into them.

By all accounts, the top echelon of producers will continue to command high eight and nine figures, as long as they’ve generated hits. But those who haven’t are believed to be in for a rude awakening. “Like, if Benioff and Weiss’ new show [Netflix’s 3 Body Problem] doesn’t work, nobody’s giving them $25 million a year for their next deal,” says a top agent, referring to the Games of Thrones duo who have yet to deliver a meaningful follow-up. “Or if Fallout doesn’t work [at Amazon], Jonah Nolan and Lisa Joy are going to have a problem.”

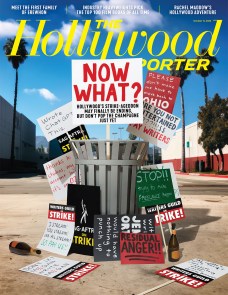

Of late, programmers like HBO have been busy quietly passing on scores of scripts and killing off development. But as writers and producers ready their first wave of post-strike pitches, buyers and sellers everywhere are talking about “ongoing,” “propulsive,” “populist” fare, which can be more cost effective and broadly appealing. Some outlets are eager for a soapier take, others want action thrillers and dressed-up procedurals.

The next Lincoln Lawyer, if you will — or The Diplomat or Hijack or Reacher. Some call it “premium light.” Others prefer “mid-TV” or simply “elevated broadcast.” Not long ago, Bela Bajaria described the ideal Netflix show as a “gourmet cheeseburger,” both “premium and commercial at the same time.” In comedy, execs say they’re prepping “hard funny” half-hours or comedies “with propulsive, character-driven narratives,” says one studio chief. Only Murders in the Building, which also benefits from star power, is cited often.

“Every outlet is looking at what they think will work, which means there’ll be fewer swings and far fewer Hail Marys,” says a second studio chief, who bemoans the degree to which safe choices are being made, many of them dependent on big stars and IP. “Financially, it’s tough for everybody right now, but everything is cyclical. Some little show will come along, and nobody will have heard of it or know anyone in it and it’ll become a giant hit that everyone will chase.”

What’s out, or at least considerably less appealing than it previously was: wistful, quiet dramedies, or “sad-coms,” as one comedy exec labels them. Period dramas have fallen out of favor, too, along with the kind of star-driven limited series that, until recently, seemed to dominate the TV dial. In recent years, the miniseries had become a surefire way to lure A-list film talent to TV, since it was a finite time commitment and could earn them top dollar. But too many executives learned the hard way that minis often don’t make financial sense, particularly when the market is flooded with them. “I mean, HBO won’t even hear limited pitches anymore,” says another prominent seller, and, by and large, insiders concur.

“I don’t think you’re going to see another $10 million to $12 million artsy limited series,” offers a top agent, citing Amazon’s twisted miniseries Dead Ringers, starring Rachel Weisz as twin OBs, as an example. A rival programmer agrees: “Big stars still matter, but the show has to be commercial or at least have that aspiration.” — Lesley Goldberg and Lacey Rose

-

Even Taylor Swift Can’t Save Theaters

Image Credit: Courtesy of Apple TV+ It may be hard to believe now, but in 2019, before COVID sent box office off a cliff, worldwide movie ticket sales hit an all-time high of $42.3 billion, including a near-record $11.4 billion in North America. While domestic ticket sales eventually clawed their way back to $7.5 billion in 2022 and may approach $9 billion in 2023, studio executives are under no illusion that moviegoing will return to pre-pandemic levels. The theatrical business is still facing an epic existential crisis.

“There is a lot of research showing that some people are now sitting on the sidelines,” says David Herrin, founder of movie tracking firm The Quorum. “It could be they became used to watching films at home or that they are fearful of being in a closed, dark space. Whatever the reasons, they are real and meaningful. The challenge for theatrical is how do studios make up for those losses?”

One veteran studio distributor has an answer: “Trying to get back to $11 billion should not be the goal. The goal should be to have a leaner, meaner business that is more profitable for the studios.”

Movies catering to adults 35 and older — whether indie players or studio-backed films including the Steven Spielberg-directed The Fabelmans — are especially imperiled. An exception was Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer, which has cleared an astounding $940 million-plus globally (the film was no doubt helped by being part of the Barbenheimer phenomenon). Herrin believes adults would come back in droves if the experience were better. “Instead of investing in at-home popcorn or silver-mining, AMC Theatres needs to invest in their theaters,” he says.

Martin Scorsese’s $200 million Killers of the Flower Moon, starring Leonardo DiCaprio, Lily Gladstone and Robert De Niro, is the next big test for an adult-skewing title. Tracking shows the film, which Apple is giving a proper theatrical release via Paramount, opening to a subdued $24 million during the Oct. 20-22 weekend (Oppenheimer arrived with tracking at $40 million). And, in an unexpected twist, Scorsese’s film will have to contend with Taylor Swift’s The Eras Tour movie, which bows Oct. 13 and hopes to be a unicorn like Barbie. In an unusual move, AMC Theatres is distributing Swift’s concert pic itself. While the project is great for theaters that are clamoring for buzzy content and get their usual take on each ticket sold (about 40 percent on a big film), it isn’t so good for studios, who lose the chance to get a lucrative distribution fee.

Oppenheimer and Barbie, which were fueled by young and older females alike, proved that consumers remain willing to turn out for an event offering. Yet the rules of what makes a film an event have changed in the post-pandemic era. All of Hollywood was stumped when Mission: Impossible — Dead Reckoning Part One stumbled. Even superhero movies are no longer a sure thing (this summer’s The Flash was a major flameout).

Robert Mitchell of U.K.-based research firm Gower Street is more optimistic than others in forecasting that global box office revenue could cross $40 billion in 2024 if the rate of growth stays the same. He concedes “if” is a big question mark, considering that next year’s release calendar could see major changes because of production delays caused by the strikes. Marvel’s Deadpool 3, for example, had to go on hiatus. At the moment, the film is still officially set to open May 3.

“The challenge for theatrical after the strikes will be the same as before and as ever in the streaming era, only more so: Make films with great cultural urgency and strong playability,” says Sony Pictures Entertainment Motion Picture Group chairman-CEO Tom Rothman. “Get over that high bar, and you will prosper. Come under it by an inch and, in the immortal words from the Wizard of Oz, you are really, most sincerely, dead.” — Pamela McClintock

-

The AI Battle Lines Are Just Being Drawn

Image Credit: Kevin Dietsch/Getty Images Guardrails surrounding the use of generative AI united creators across Hollywood and proved to be a major point of contention in negotiations between the WGA and studios. In its deal with the AMPTP, the WGA secured some protections for members that guarantee credit and pay for their work regardless of whether AI tools are utilized in the process. But absent in the agreement is any mention of whether the studios can use writers’ material as training data — a hotly contested point in bargaining.

The recently ratified WGA deal, which acknowledges the legal landscape as “uncertain and rapidly developing,” says that both sides reserve all rights to pursue litigation on the issue. It appears that studios maintain that they are allowed to do so and plan to follow through. “The companies have, they claim, some ongoing copyright rights in using our material,” negotiating committee co-chair Chris Keyser told THR on Sept. 27.

Even as studios battle with writers who do not want to provide the raw materials to build the tools that they fear may one day replace them, AI companies are scraping the internet for copyrighted works owned by those very studios as training data. This is happening as artists and authors are suing such companies as OpenAI and Meta, alleging that mass-scale copyright infringement is fueling their AI ambitions.

One question at the front of writers’ minds: Why aren’t studios allying themselves with scribes and against AI firms to oppose what could constitute the pilfering of their material in violation of intellectual property laws? Studios own most of the copyrights on their works because of their relationship with writers as works-made-for-hire. They may choose to step off the sidelines and join the legal fights that will decide the legality of using copyrighted material as training data.

“Studios should be protecting copyrights,” says one WGA member. “That’s their work too.” This person notes this is in the studios’ interest, as they will “never be able to compete with Google or OpenAI or Meta.” Adds Darren Trattner, an entertainment lawyer who represents actors, directors and writers, “The studios could align themselves with writers, because there’s a common interest.”

In the not-too-distant future, AI companies might turn to competing with studios by deploying generative AI tools to pen and polish scripts (writers will still need to play a part in the process given that copyrights can be granted only to humans). Some of them that are considered leaders in the field with troves of cash to build up their tech — including Apple and Amazon — already own companies that are a part of the AMPTP. The legacy studios, if they intend to train their own AI systems on writers’ material, are likely at a major disadvantage.

“Why would a studio want 100 years of films to be gobbled up by third-party AI programs?” Trattner asks. “Then, anyone can use and try to create material based on their intellectual property.” — Winston Cho

-

The Kids Are On YouTube and TikTok

Image Credit: Steve Granitz/FilmMagic All the aforementioned belt-tightening doesn’t address a bigger problem for legacy media companies and such insurgents as Netflix and Amazon. Competition for potential viewers’ time has never been more intense, and TV — in all its forms, but especially broadcast and cable networks — isn’t winning the battle.

Linear TV’s audience is old, and it’s extremely unlikely to get younger. Outside of (some) live sports, a show on broadcast or cable TV is lucky to draw even 2 percent of adults 18-49 — the demographic for which advertisers usually pay a premium to reach — without the aid of multiple days of streaming and DVR playback (which may not involve ads).

As for teens and younger adults? They’ve found other things to watch. The majority of TikTok users are under 30, and they spend a lot of time on the app. TikTok users in the United States averaged more than 80 minutes a day scrolling through videos, according to a 2022 report from market research company Sensor Tower. YouTube users also spend more than an hour a day on the platform, where the biggest channels — ranging from MrBeast to Cocomelon — have more than 100 million subscribers worldwide. The biggest video game releases outearn blockbuster movies.

Streaming falls somewhere in between, with a user base younger than that of traditional television but older than that of TikTok and some other emerging platforms. It’s also the default TV-watching vehicle for the largest share of Americans, according to Nielsen, capturing 38.3 percent of TV usage in August, as compared to 30.2 percent for cable and 20.4 percent for broadcast. This means that such companies as Disney, Warner Bros. Discovery, Paramount Global and NBCUniversal are investing billions of dollars chasing bigger pieces of that 38 percent (of which YouTube and Netflix regularly make up almost half). It’s a cost that makes sense — they need to be where viewers are — and also acts as a drag on their bottom lines.

The big media companies that dominate Hollywood built themselves on the idea of a captive audience. That audience has broken free and scattered to thousands of corners. The challenge ahead — one that no single company seems to have solved — is to get into enough of those corners to win that audience back. — Rick Porter

This story first appeared in the Oct. 11 issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine. Click here to subscribe.